How do apologies affect children's feelings and behavior?

Most parents want their children to learn to say “I’m sorry” – but many parents wonder what these words really mean to young children. This research considered whether children feel differently in the presence or absence of an apology, and whether children view prompted and spontaneous apologies differently.

In one study, we examined whether children feel and behave differently in the presence - versus absence - of an apology.

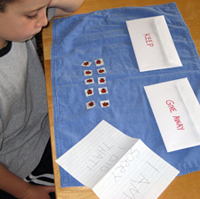

Children, aged 4-10 years, received stickers in an envelope from ‘a child in a different city’, and were asked how the stickers make them feel and think. However, the study involved deception: the envelope was actually prepared by the experimenter and contained no stickers, but rather a note from the fictional gift-giver saying that s/he had used all of the stickers before sending the letter. Some notes offered an apology (i.e.: “I’m really sorry.”), while others did not.

Deception was necessary in order to effectively test the impact of apology. After opening the envelope, children were asked questions about their feelings, the traits of the gift-giver, and how the gift-giver might have felt. Children were then given the opportunity to share some new stickers with the gift-giver. At the end, all children choose some stickers to take home.

Many parents wonder what apologies mean to their children. Our previous work showed that children as young as four years are aware that apologies have emotional implications for people who have been upset. However, we had only tested this by telling children hypothetical stories. This experiment was the first that examined how real apologies affect children’s feelings, judgments about a transgressor, and willingness to share.

Another study compared children's reactions to situations involving either a spontaneous apology, a prompted apology, or no apology at all.

In the study, children, ages 4 to 8 years, heard two stories that showed one character pushing or grabbing to get a desired object. In both stories, the child saw one of three possible behaviors from the character that committed the transgression (e.g. the child that pushed): no apology, spontaneous apology, or adult-prompted apology.

Children were asked questions about the feelings of the transgressor and the victim (e.g. How does the victim feel at the end of the story?) An understanding of mixed feelings was also explored (e.g. do children understand that a victim who hears an apology might feel both good and bad?).

Many parents wonder whether prompted apologies mean something different to their children than spontaneous ones. In this study, we found that even preschool-aged children possess two key understandings about the emotional effects of apology: that apologies are expressions of remorse and that apologies can be effective in soothing another person’s feelings. However, the effects of apology did not carry over to children's moral judgments; children were equally as likely to characterize a non-apologizing and an apologizing transgressor as "nice".

Interestingly, we also found that the word "sorry" is not needed for children to understand the emotional benefits of apology for the "victim" of a transgression. Simply knowing that an apology was delivered was enough for young children to see remorse in a transgressor and improved feelings in a victim.

Most recently, a study has explored whether children are aware that certain types of apologies are not genuine, and considered whether children view these types of apologies as less effective (or even damaging).

In this study, children ages 3-8 hear an experimenter read two short stories. In each, the main character transgresses (misbehaves) to get something s/he wants (e.g., pushes another child to get a toy). In these stories, children see one of three things:

- No apology from the transgressor

- An apology from the transgressor that is offered without resistance

- An apology from the transgressor that is given very reluctantly after an adult prompt

After each story, children are asked what they think the characters will feel. We are interested in whether children think that unforced apologies convey more remorse and do more good than forced apologies (or no apology at all).

In this study, we anticipate that children’s age will affect how they view the types of apologies that we show them. We expect children from 3-8 years of age to know that a non-forced apology is better than no apology at all. However, we expect older children to be more aware than younger children that a forced apology can be just as bad as not apologizing. When complete, this latest research may give us more insight into how adults should approach prompting apologies from their children.

For more information about this research, contact Craig Smith, Living Lab collaborator now at the University of Michigan.

Resources:

Try it at the Museum

Puppet Play

Have your child wear one of the animal costumes and find the corresponding “baby” animal (puppet). Play the part of the baby yourself and interact with other baby animals in the space. When your baby animal does something wrong, ask your child how your baby animal could make the situation better. Have your child prompt the baby animal to apologize. Ask how each animal feels now. Did the baby animal really mean it? Does it matter how old the animals are?

Try varying whether the apology occurs right away or after a pause. Do your child’s ideas about the animals’ feelings change?

Try it at Home

Apology Stories

Create two stories with your child using three dolls, action figures, or stuffed animals as props. Make one of the three toys be a parent, and the other two siblings. In both stories have one sibling (transgressor) take a toy away from another sibling (victim) without permission. Next, choose an ending for your story. In one story have the transgressor apologize after making his/her sibling cry. In another story have the transgressor apologize after the parent tells the transgressor to do so.

Ask your child in each story if the transgressor really “meant it” when s/he said “I’m sorry.” Does your child differentiate between a spontaneous apology and an adult-prompted apology, or view them as the same?

Role-playing studies with older kids and adults have found that people modify their apologies to fit the offense: more elaborate apologies come after more serious transgressions. Try acting out some more pretend transgressions with dolls or stuffed animals. Does your child change the complexity of his/her apology to fit different types of problems (e.g. an accidental bump vs. breaking someone’s favorite toy)?

Apologies from Characters in Story Books

The next time you are reading a book or watching a show with a transgression and apology in it, pause to ask your child what they think about the situation. Did the transgressor really mean it when they said, “I’m sorry”? How do you know? Did the transgressor need to be prompted before they apologized? How does the victim feel? See if your child reacts differently depending on which character they like more, the transgressor or the victim.

A further conversation can explore questions like “Why do we apologize for things?”.