Can children perform intuitive algebra?

Previous research had shown that children - and even infants - think about numbers long before entering school. For example, preschoolers know that when they see five objects, then see five more added (5 + 5), the outcome is more likely to be 10 than 6. This study investigated intuitive math abilities - in particular, whether young children can use their intuitive sense of number to figure out an unknown quantity, a skill that is the basis of algebra.

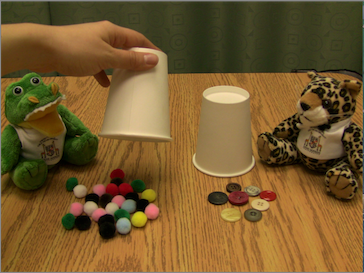

To find out whether children (ages 4 to 6 years) have algebraic intuitions, the researchers showed them simple stories with unusual props. They introduced children to two furry friends: Gator and Cheetah. Gator and Cheetah each have a “magic cup” which adds items, like buttons or pennies, to a pile. Gator’s magic cup always adds one amount, and Cheetah’s adds a different amount. Children saw the pile before each magic cup adds its items, and the pile afterward, but they never saw what was in the magic cups. In the end, the researcher pretended that she had mixed up the cups. She showed the child what was inside one cup and asked them to help her figure out if it was Gator’s cup or Cheetah’s cup. The majority of the children knew whose cup it was, showing that young children had been solving for a missing quantity: they were doing basic algebra!

The children were not using memorized rules and symbols, like older children in algebra class, but rather their “approximate number system”. Our approximate number system, or number sense, is our gut-level inborn sense of quantity and number. Humans and other animals use this ability to unconsciously think about the quantity of objects around their world. This number sense is developed well enough to allow children who are 4, 5 and 6-year-olds to do basic algebra.

This study found no difference between boys and girls in their intuitive math abilities. Children of both genders used their approximate number sense to solve simple algebra problems.

This research shows us that young children are capable of abstract reasoning, and can help teachers, parents and other grownups understand what kinds of mathematical thinking young children spontaneously engage.

For more information about this research, contact Dr. Melissa Kibbe. Dr. Kibbe conducted the research described above in Living Laboratory at the Maryland Science Center, as a member of the Laboratory for Child Development at Johns Hopkins University. Now director of the Developing Minds Lab at Boston University, Dr. Kibbe continues to research children's reasoning about algebra, and collaborates with Living Laboratory at the Museum of Science, Boston.

The research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NIH R01 HD057258), with additional support from the National Science Foundation under Award #1113648 to the Museum of Science, Boston.

Resources:

Try it at the Museum

Most museum spaces for children feature an activity with ramps and balls. Encourage your child to use the ramps to move the balls from one side to the other. What happens when you change the angle of the ramps? Can you make the ball move faster or slower? How few pieces can you use to accomplish your goal? Are their other ways your child is engaged in mathematical problem solving?

Try it at Home

Play Number Estimation Games:

Gather a quantity of small items (like cereal or raisins) and two cups. Have your child watch as you place five objects one at a time into one cup, and ten into the other. Ask the child to show you which cup has more. Then play again, but make the quantities more similar (five objects in one cup and seven in the other). How did changing the quantities affect your child’s estimation?

Object Arithmetic:

Put five objects one at a time into one cup and ten into the other. Now add ten more objects to the first cup and one to the second. Ask your child to show you which cup has more, and why. Did your child use number strategies like counting, or did they rely on numerical intuition?